The next two fake teens in this series were “serial teens”, people who posed as teenagers over and over again in multiple locations for reasons that are barely comprehensible.

Treva vs. Brianna

In the spring of 1997, a teenager turned up at Glad Tidings Church in Vancouver, Washington. She was a tall, solidly built girl with brown hair plaited into old-fashioned braids. She said her name was Brianna Stewart, she was 16 years old, and she was homeless. She had been on her own for two or three years, hitchhiking from state to state in search of her biological father. All she knew was that he lived somewhere in the Northwest.

Her mother had been murdered when she was just a small girl, Brianna said (later, she told a boyfriend her stepfather was the killer). This left her in the care of her tyrannical, sadistic stepfather, a Navajo Indian who tortured her, molested her, anf forced her to appear in child porn he produced. Thanks to his close ties with local police, he was beyond the law. That’s why Brianna ran away from Alabama.

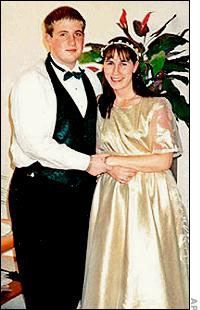

This story moved the heart of a church secretary, Debbie Fisher. She and her husband, Randy, immediately offered Brianna a place in their home. That autumn, Brianna enrolled as a sophomore at Evergreen High School, where she gained sympathy and respect as a former street kid with a dark, violent past. Aside from the unusual braids and her habit of wearing bib overalls, Brianna seemed like a wholly normal teen. She was a bit klutzy and awkward. Her grades weren’t remarkable. She joined the school tennis team, hung out at the mall, and won a walk-on part in the Evergreen production of Man of la Mancha. She loved Romeo + Juliet and moony poetry. Soon she had an adoring boyfriend, 15-year-old football player and aspiring actor Ken Dunn. He accompanied Brianna to Glad Tidings with her foster family every Sunday morning, drove her wherever she wanted to go in his ’78 El Camino, and listened for hours to stories of her troubled life. He described their love as “the perfect teenage romance.” For Christmas, he gave her a silver ring engraved with “I love thee”.

The stories Brianna told the Fishers were astonishing to a straight-laced, Christian couple. Her stepfather was the high priest of a Satanic cult outside Mobile, and before she broke away from him he had been training Brianna to become the high priestess. He impregnated her when she was barely a teen, and she miscarried after he shoved her down a flight of stairs.

Somewhere in the Midwest, she had volunteered to work on a senator‘s re-election campaign. That man also got her pregnant.

Brianna told Ken that some of her stepfather’s cronies knew her whereabouts and were following her, which terrified him.

She also told stories of her stepfather running guns from the Ivory Coast and trafficking in drugs. She talked of an albino grandfather from Romania. She said she had found a man named Michael Stewart living in Aloha, Washington, and contacted him in the hope he was her real dad. He wasn’t, and he turned out to be almost as deranged as her stepdad. He kept Brianna prisoner in his home for two months, drugging her with crack.

Her greatest desire, Brianna told everyone, was to finally have a normal life.

Brianna was too afraid of her stepfather to report his crimes, but she would see justice served for one horrific event in her life. Shortly before she found Glad Tidings, Brianna had reported being raped by a middle-aged security guard named Charles Blankenship.

In March of 1998, Blankenship would be convicted and sentenced to a year for statutory rape.

Brianna’s normal new life in Washington was nearly perfect until the middle of her junior year. That’s when the first suspicion about her age was voiced, by a dentist who found it odd that Brianna’s wisdom teeth were already gone. Ken and the Fishers confronted her, and she responded with such angry indignation that they left the subject alone.

She became accusatory toward the people around her, showing a strong paranoid streak; friends were spreading rumours behind her back, teachers weren’t giving her the grades she deserved, Ken thought he was too good for her after snagging the lead in Fiddler on the Roof. All of her relationships eroded. She argued viciously with the Fishers over chores. They asked her to leave their home in May 1998. She was placed in foster care. Again, a dental exam led to questions about her true age, and social worker Jan Shaffer confronted her. Brianna responded with the same fiery indignation, firing off a letter to the state Department of Social and Health Services. She wrote, “I feel that remaining in foster care is not safe for my physical, mental and emotional well-being. I feel that I have been abused by the very system that I asked for help.”

In the autumn of ’98, Brianna was taken in by another local family, David and Theresa Gambetta. Five months later, her paranoid streak re-emerged with a vengeance. She accused David of placing mini-cameras in the lightbulbs to spy on her. Gambetta was cleared of any wrongdoing, and Brianna was homeless once again.

In May, Portland, Washington police officer Richard Braskette and his wife Virginia took Brianna into their home. Just like the Fishers and the Gambettas, they were moved by her helplessness and felt they could give the girl some of the stability she needed to succeed in life. After all, she wasn’t your average street kid. Throughout all the turmoil of her junior and senior years, Brianna had tenaciously held on to her dreams. She wanted to become an attorney and a children’s rights advocate, so she would have to earn her way through college. That meant finding some way to acquire a Social Security Number, without a birth certificate or any other form of government ID. She wrote letters to reporters, victims’ rights advocates, even the governor and Montel in search of assistance. Because Brianna didn’t know her place of birth, no one could help. She said the FBI had tried and failed to find any proof of her identity (which turned out to be false). Finally, she sued the state’s Bureau of Vital Statistics, demanding they issue her a birth certificate.

In late 1999, still desperately seeking proof of her identity, Brianna traveled to a town she suspected could be her birthplace: Daphne, Alabama. Friends donated money for the trip. She said that her memories prior to age 4 were extremely hazy, and she wasn’t entirely sure Brianna was her true name. Some therapists suspected she was suffering some form of traumatic amnesia. Brianna herself suspected she may have been abducted by the people she knew as her parents.

A local police officer toured Daphne with Brianna, helping her search for places she might remember. A few spots looked familiar to her, but no relatives or documents surfaced. The trip was a bust.

Brianna also traveled to Montana to investigate the possibility she was a girl who had gone missing in 1983.

Throughout this trying time, Brianna received strong moral support from her school counselor, members of her church, and Evan Burton, an advocate at a Portland drop-in center called Greenhouse.

In June 2000, Brianna joyfully graduated from Evergreen High with the rest of her class. She began scouting prospective colleges, though her identity issue was far from resolved.

For help with that, she turned to the law. A Vancouver lawyer petitioned the government on her behalf, while Portland attorney Mark McDougal apparently worked on her case pro bono, perhaps happy to do a favour for a plucky, hard-luck kid.

Excellent news came from the Vancouver attorney: A deputy state attorney general said the state wouldn’t oppose Brianna’s petition for a birth certificate, if she appeared at a court hearing scheduled for March 2001. The end of her long, hard-fought battle was in sight.

Then the other lawyer, McDougal, made a simple request that should have been made much earlier in the game; he asked that Brianna be fingerprinted so he could submit her prints to the FBI.

The results of that one simple request brought Brianna Stewart’s tireless campaign to a halt…almost. Her fingerprints matched those of Stephanie Danielle Lewis, a woman arrested in Altoona, Pennsylvania in 1996.

And “Stephanie Lewis” was really Treva Joyce Throneberry, a 31-year-old Texas native.

Brianna insisted the FBI had made a mistake. Frustrated and angry, she went to Greenhouse and told Evan Burton the whole story.

Burton had stood by this girl during her struggle to make a normal life for herself, but now the vague doubts at the back of his mind burst to the fore. Something was very wrong with this picture. Brianna did look much older than 18. And if she was in her 30s, as the FBI claimed, that meant Charles Blankenship had been convicted of statutory rape for having sex with a full-grown woman.

Burton called the police.

Detective Scott Smith, the same officer who arrested Charles Blankship two years earlier, was assigned to the Brianna Stewart case. Piece by piece, he put together the story of a fragmented life that began in Electra, Texas and traced a jagged trail through numerous states before landing in Vancouver, Washington. Nothing about this life was simple.

Unlike Brianna Stewart, Treva Throneberry was not from Alabama. She had siblings. She knew her natural father.

Treva was born to Carl and Patsy Throneberry in 1969, the youngest of five kids (one son, four daughters). They were raised in Electra, Texas, where Carl made a modest living as an oilfield truck driver.

As a teen, Treva played on the high school tennis team and waitressed part-time at the Whistle Stop drive-in. She was quiet, sweet, good-natured. She was also unusually devout, reading from her Bible at every opportunity and attending services at a Pentacostal church that her parents considered cult-like.

She occasionally exhibited signs of paranoia or a deceptive nature even then. Her niece recalled Treva waking her in the middle of the night with a strange story about a gun-toting intruder lurking in the house, which wasn’t true at all.

In December of 1985, 16-year-old Treva walked into the Electra police station and reported that Carl had raped her at gunpoint. This was the first of many rape allegations she would make.

Treva’s sisters and niece say they, and Treva, were sexually abused for years by their late uncle, but insist Carl Throneberry would never have done such a thing. Carl and Patsy believed the “cult” had somehow manipulated the girl into accusing her father.

The three older girls married as teens, putting themselves beyond their uncle’s reach.

Treva was placed in the foster home of Witchita Falls schoolteacher Sharon Gentry. She appeared deeply disturbed, knocking her head against walls in her sleep and speaking frequently of suicide. She also told bizarre tales of being abducted by a Satanic cult, lashed to a stake, and forced to witness the ritual sacrifice of cats and dogs. She would later tell similar stories to her sister, Kim, but replaced the animals with human babies.

Treva was soon committed to Witchita Falls State Hospital. She never received a definite diagnosis. After six months of treatment, she was placed in the Lena Pope Home for Girls in Fort Worth, and enrolled as a senior at Arlington Heights High. She graduated in June ’87.

The charges against Carl Throneberry were ultimately dropped for lack of evidence.

Treva briefly visited her sisters the year after her graduation. They wouldn’t see her face again for 13 years, when it appeared on TV and in newspapers.

During that time, Treva wandered from state to state, depending on the charity of strangers for shelter and food. Only two things remained constant in her life: She never used the same name twice, and she was always a runaway teenager. The details of her sad, disturbing stories varied, but there was always hideous family violence and rape involved. Sometimes there were cults that butchered children and animals. Detective Smith charted her peregrinations as thoroughly as he could, but there would always be gaps in the record of Treva’s odd existence.

– 1992: 19-year-old “Keili Smitt” lived with a family she met at a church in Corvallis, Oregon. She told police she was on the run from her father, who had caught up to her once and raped her in his car. Keili left town before the man was located.

– 1993: A teen girl surfaced in Portland, Washington and reported that her father, a local police officer, had raped her. She vanished before the investigation was complete.

– 1994: “Cara Leanne Davis” arrived in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, after fleeing her father’s violent Satanic cult.

– 1995: 16-year-old “Kara Williams” told social workers and police in Plano, Texas about her life in a Satanic cult. She had been forced to pray to Satan every night, and was told she would someday drown in a lake of fire. Most of her childhood friends had been ritually sacrificed. Her father, a Colleyville police officer, had gotten away with murdering her mother. “There was nothing in her behavior or presentation to suggest that she was knowingly misrepresenting the facts,” a psychologist observed.

Kara was placed in several foster homes and youth shelters while social workers scoured the area for her monstrous father. She attended three different high schools. In an effort to help her settle down to something resembling normalcy, her caseworker bought a new tennis racket for her.

In September, a youth home staff member grew suspicious of Kara and uncovered the fact that she was 26-year-old Treva Throneberry. Despite her tearful protests that she was not Treva, a court discharged her from government care.

– 1996: 16-year-old “Emily Kharra Williams” told police in Asheville, North Carolina, she was running from a Satanic cult in Texas.

Later that year, 16-year-old “Stephanie Lewis” told an assistant district attorney in Altoona, Pennsylvania that she was on the run from an abusive Satanic cult to which her father belonged. She was lodged in a local youth home, where a caseworker discovered papers linking her to people in Texas and to her true identity. Charged with giving false information, Treva spent nine days in jail.

Back in Texas, a weird rumour surfaced that Treva had been killed in the Branch Davidian conflagration. Sharon Gentry sent her dental records to Waco to ascertain if Treva was among the dead.

On March 22, 2001, just days before the court hearing that would help make Brianna Stewart a legal adult, Treva Throneberry was arrested at the Portland YMCA and charged with theft and perjury. She had defrauded the foster care system, the courts, and Evergreen High for nearly four years.

Her former classmates, teachers, and caregivers were stunned. She had seemed so average: average grades, average tennis skills, average tastes. Ken Dunn, then employed at Disney World, was boggled to realize that his Sadie Hawkins date had been pushing 30. He had begun to doubt Brianna’s incredible stories when she accused David Gambetta of spying on her with cameras, and he had gently questioned her about her age after that first suspicion was aired by Brianna’s dentist, but he had no idea she wasn’t a teenager.

Charles Blankenship was probably relieved. The “minor” he had confessed to having sex with had really been 28, and his conviction was erased.

Once again, Treva vehemently insisted she was not Treva Throneberry. She rejected every piece of evidence. She insisted on a DNA test to prove she wasn’t the child of Carl and Patsy Throneberry, which of course showed an extremely high likelihood (99.93%) that she was. Even this result she denied. She refused a plea deal that would have given her a short sentence (2 years) in exchange for a confession. Nor would she allow her court-appointed attorneys to argue that she was delusional; she fired them rather than use such a defense.

At her November trial, Clark County senior deputy prosecutor Michael Kinnie argued that Treva was far from delusional. She was a skilled, cunning conwoman.

Kenneth Muscatel, the psychologist hired by the court to examine Treva, concluded she was disturbed yet competent to stand trial.

Treva’s mission in life remained the same: To prove she was Brianna Stewart, 19. In her Clark County jailhouse cell, she hit the law books hard.

“Brianna” often showed up for court with her hair in two braids. She represented herself to the best of her ability.

Sharon Gentry traveled from Texas to testify for the prosecution. She presented photos of a younger Treva and herself on vacation, and Treva examined them before calmly declaring it wasn’t her. She then asked her former foster mother what Treva was like. Gentry’s heart turned over as she described a polite, hard-working, “wonderful” young woman. It seems Treva couldn’t resist the opportunity to learn what others thought of her.

“Was Treva smart?” she asked.

Gentry replied that Treva studied hard and received good grades.

Other witnesses testified to Brianna’s eagerness to establish her identify so she could get an education and become financially independent, but no one testified that she was who she said she was. No one, except perhaps Treva herself, believed that.

Treva was convicted, and judge Robert Harris regretfully sentenced her to three years. He would prefer to send her to a state hospital for treatment, he explained, but the Washington prison system was already overtaxed with mentally ill prisoners.

Treva’s family had more or less given up on her. They found their own ways to comfort themselves after her story hit the media. Patsy firmly believed that Treva had attended her grandmother’s funeral in 1998, disguised as an old woman. Carl claimed that Treva had phoned him a few times over the years, pretending to be someone else, just to touch base with him.

Upon her release from prison in 2003, Treva remained in Washington as Brianna Stewart and continued her fight to be recognized as the girl she had created. She appeared on ABC’s Primetime program, sans braids, to explain that the DNA tests had been flawed.

“Brianna” has not spoken publicly since then, but online comments such as one by “concerned friend” argue that the court covered up evidence of Brianna’s identity. It is entirely possible that “Brianna Stewart” herself wrote them.

One thread seems to run through several of these cases: childhood sexual abuse. Some people recover from it, and others are profoundly damaged.

Very true.

Wow, incredible. I will admit that I find these fake teen tales fascinating for all that they are also sad and disturbing. Have you blogged about Tina Resch? I thought you had – it's a very sad story that involves deception – but when I searched I couldn't find anything on your blog.

Hi,Just saw your blog in my stats – just did a thing you might like or not like – http://barfstew.blogspot.com/2011/03/new-time-traveler-hipster-found-in-1915.htmlRick

This story really hits me because it is so similar to the behavior and stories of a girl that my wife and I helped out who was also homeless and bouncing from home to home. I don’t know anything about sexual abuse, if it happened, she’s never admitted to it. But she was diagnosed with traumatic amnesia and has trauma-related memory problems as well as severe ADD that requires medication so that she can handle basic life tasks like paying rent. She was homeless a lot. She also would knowingly embellish stories because she thought they sounded more sympathetic. She was also diagnosed on the autism spectrum (something I can definitely confirm from meeting her–I have two brothers on the spectrum) so her idea of whether the truth or a lie was a better “story” was probably quite off. Unlike Treva/Brianna, my wife had contact with her online for years and after a lot of struggling she was able to get her real birth certificate duplicate and a state ID. AFAIK, she’s never falsely accused anybody of a crime, did start college but dropped out due to major depression, and I hope is too intelligent to engage in a parasitic existence like Treva. I think Treva probably had the delusion that if she could start over with a new identity and erase the old one that she could have the normal life she dreamed of. But the paranoia (including about sexual matters) followed her. The paranoid personality disorder is a doozy. The girl I’ve been helping actually worked in sex work for a while (this is not a story, she did this while we were supporting her, with our approval, if not enthusiastic approval–in fact, she lost a living situation due to one of her online “friends” outing her to the couple who was housing her before, resulting in a prolonged bout of homelessness) although she seems to have exhausted her earning potential there and is looking for a better source of income, and also has carried on personal relationships so, in the end, I doubt she was sexually abused. Just emotionally abused severely and exploited by her parents. One used her as unpaid labor in his scams/business, and the other would verbally berate the fuck out of her because she considered her an unwanted burden and trash because of her mental disability. So you can have PTSD even without sexual abuse. All it takes is a pair of particularly vile, cruel parents. The final act in her mother’s abuse was to manipulate her into not telling the authorities that she’d been kicked out as a minor because CPS would come in and probably take the younger siblings away. Of course this denied her and her informal foster parents the resources she needed during the last year of high school, but, as a minor, she lacked the judgment to realize this was a bad decision.

What a strange story. Bless you for trying to help her, but I have questions. For example, did you ever meet her “vile, cruel” parents, and hear their side of the story? Where did you get all this information about her from, aside from herself? It seems at least possible that she was conning you more than you think, for support and emotional involvement more than money. Not everyone would support a strange young woman in her prostitution activities, for example. But maybe something in her stories, like claiming or pretending to be autistic or have PTSD, made you more sympathetic or an easier mark than you might otherwise have been.

Ms. Throneberry’s story was later dramatized in the Law & Order: Special Victims Unit season 8 episode, “Pretend”, although the version there only used the whole SRA angle for a minor plot point early on, and simply portrayed the character as someone who got so comfortable in the foster care system that she never wanted to leave it.